I’m a little embarrassed to admit that Pom Poko was my first ever watch from the now ever-present Studio Ghibli. A comrade recommended it to me after a discussion about eco-terrorism, but after realizing it would cost $3.99 to watch, I was a little hesitant to make the investment. I’ve never really been one for animated movies, and the tag of “For Kids” made me question its thematic potency. But, going out on a limb, I decided to say “fuck it” and go for it anyway. AND BOY WAS I GLAD I DID.

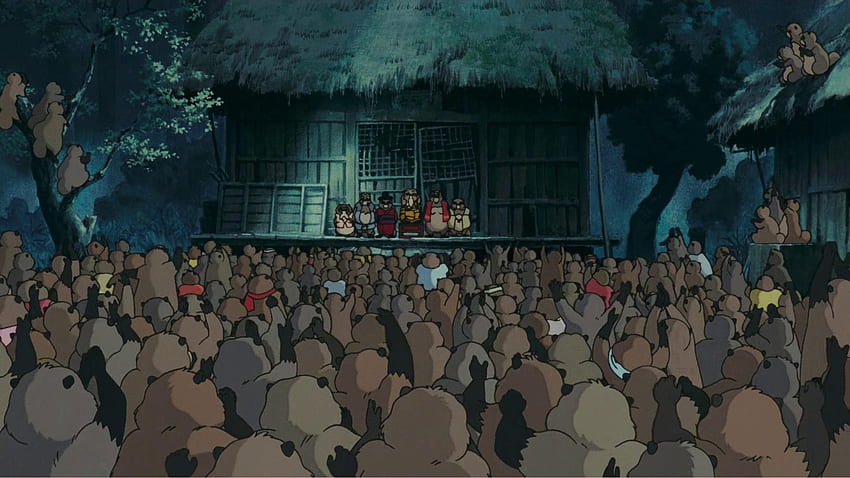

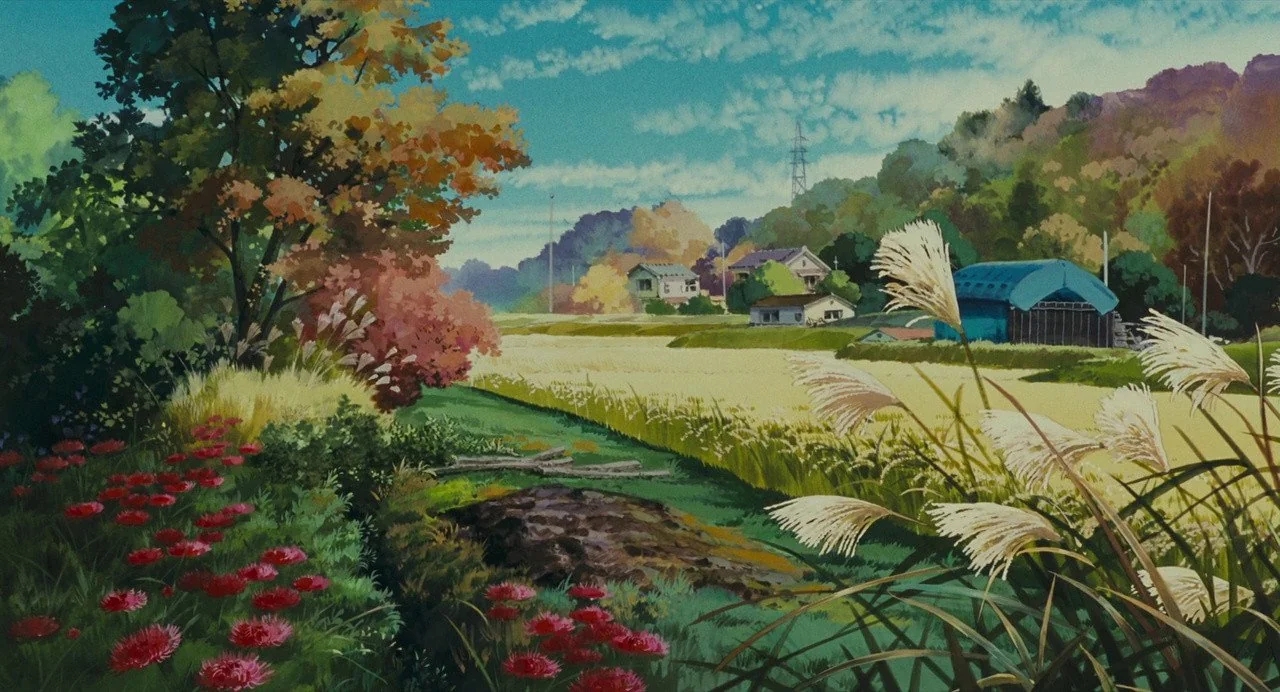

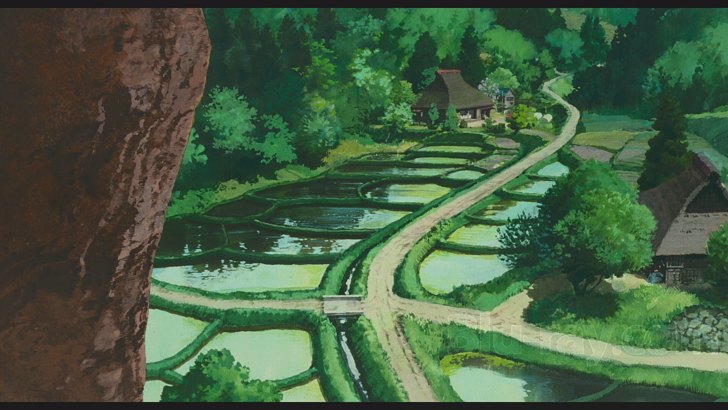

Released in 1994, the movie’s primary subject are the Tanuki, a Japanese raccoon-dog ridden with folk-lore. Set in Tama hills, an undeveloped area outside of Tokyo, the Tanuki are threatened when human development begins to encroach on their home. After initially fighting each other for the dwindling food and space, they unify around the matriarch Oroku and plan to resist the construction. Their strategy hinges on a magical forgotten power to shape shift, an idea taken straight from the Japanese lore surrounding them.

Masterfully, it addresses eco-terrorism, the pitfalls of collective action, and the simultaneous futility but necessity of resistance, all while remaining light enough of a watch that it can still hold the tag of “For Kids”.

As the destruction of Tama hills progresses, so do their tactics. Competing approaches emerge, among which direct violent action against the humans and their nature destroying implements is the first one taken. The insurgents, led by the stubborn and combative Gonta, lead trucks to drive off cliffs, smash industrial machinery, and stage direct confrontations with police. In an epic sequence near the end of the movie, Gonta and his soldiers use their massively inflated shape-shifting testicles to batter riot police (I was pleasantly surprised to learn that the Tanuki’s “golden balls” are a symbol of wealth in Japanese folklore).

The approach of direct action, either via property destruction (sabotage) or eco-terrorism (direct action with the intent of terrorizing a general population) is one that has been underexposed but long practiced by social movements – for a longer history of this, I would highly recommend Andreas Malm’s How to Blow Up a Pipeline (it’s free 😉). The movies depiction loosely follows the pattern of ecologically minded sabotage in the real world. Initially successful, but the barrier to entry so high, the personal risk so great, and the absence of a sustainable mass movement to preserve its gains often leave it vulnerable to a noticeable but short-lived effect. This being said, through a particular lens the actions of Gonta are by far the most effective at delaying the Tanuki’s extinction.

Another tactic employed by the forest dwellers consists of not harming but scaring the humans. By transforming into various phantasmal “goblins” they are successful in driving away small groups of workers who are so frightened that they quit. Unfortunately, the never-ceasing tide of labor proves their attempts futile as each worker scared away is soon replaced by a new one. Here, we might see their illusions as analogous to traditional conceptions of non-violent protest. By displaying a hypothetical show-of-force via mirage, they threaten the ruling class with the possibility of mass resistance. But, by this point in the movie, all sabotage by Gonta’s crew has ceased, and thus, without any physical direct action to back up their hauntings, business as usual proceeds.

One of the final attempts by a splinter of the group consists of an appeal to the human press, which ultimately delivers the Tanuki public sympathy, but which ends up being far too little, far too late. The narrator states that the concern for their plight results in a few parks being constructed where small groups can survive, but this is a pittance after most have been driven from their homes. Here, Pom Poko reveals the danger of relying on the oppressor for salvation. Though advocacy and lobbying might deliver small, short-term gains, ultimately only the collective power of the oppressed can protect its own future.

In a final act of resistance they create a temporary mass-mirage, turning their now barren landscape back into their once abundant home. Importantly, they not only imagine the physical aspects of the land they have lost, but also the culture and community that lived on and with it. In the fight for a world so radically different than our own, it is hard to imagine a scene more necessary to our struggle than this one. A desperate act of collective imagination in the face of overwhelming odds – a final assertion of agency before their destruction. And, even though this one isn’t totally successful in stemming the crawl of human destruction, a different one might very well be.

A beautifully animated story with ever-relevant themes, it is an absolute must-watch for any environmentally minded socialists (which should be everyone but hey, we’re all busy). In the context of both our campaign at Furman for democratic control, as well as within our national and global context of the fight against Fossil Capital, Pom Poko offers a depiction of modes of resistance that will remain timeless as long the planet continues to burn.

PS. Here’s the Youtube link – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XHo8Frm8IGI

Leave a Reply