Twice now, our university president, Elizabeth Davis, has quoted the American critic and writer James Baldwin. In both her end-of-semester letter, “A Season of Hope,” and a video titled “Happy Holidays from Furman University,” she has included the following:

The writer James Baldwin said, “The hope of the world lies in what we demand, not of others, but of ourselves.” Furman’s values call us to meet the world’s challenges with courage, moderation, justice, wisdom, and humility. And, I would add, with hope.

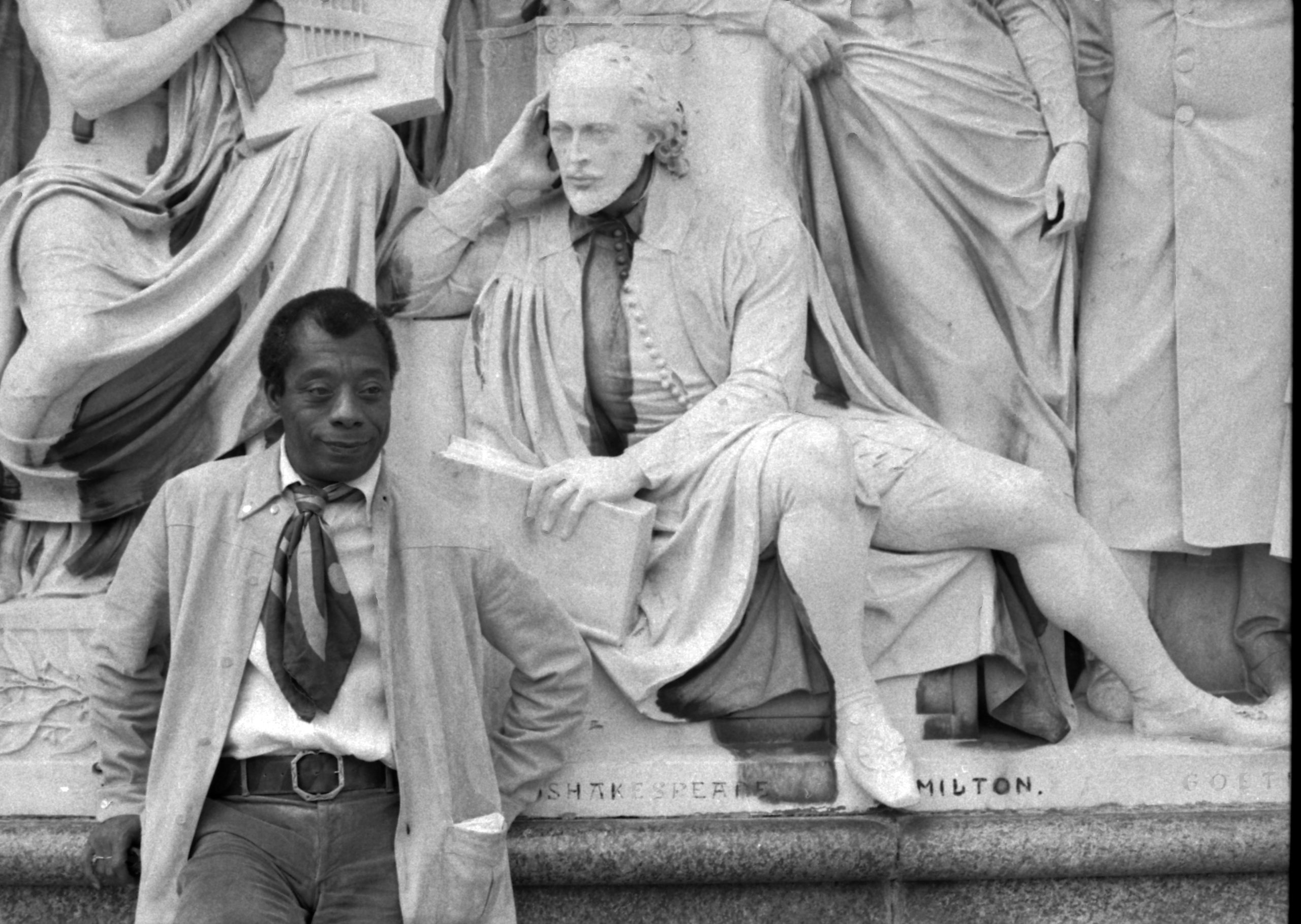

I, for one, was initially excited to see Davis reference a writer as poignant and revolutionary as Baldwin. His essays, poetry, fiction, and participation in debates on Civil Rights defined a generation of radicals, and his frequent sparrings (as well as relationships) with movement leaders like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. codify his place as a canonical thinker of the time. Suffice it to say, in reading Davis’s seasonal reflection, I experienced a momentary glimpse of hope.

This was unfortunately cut short by the moment it took to me realize that Davis is not quoting Baldwin as he would have defined himself, a shameless critic of white America, but rather as an airport bookstore spectacle, another radical whose poetics are neutered by white liberals wanting to sound profound but entirely misappropriating the content of their messages.

Let’s begin by examining the context of Baldwin’s quote. It is (and I do not say this sarcastically) ripped from what can only be described as a eulogy published in Esquire after Martin Luther King’s murder in 1968 titled “The Shot That Echoes Still.” In the first section, from which Baldwin’s plea has been stolen, the pain of a movement can be felt in his prose. He is openly struggling to balance his belief that “every human being is an unprecedented miracle” with the tragedy, horror, and injustice of the moment.

One tries to treat them as the miracles they are, while trying to protect oneself against the disasters they’ve become.

Here is a man trying to reconcile revolutionary humanism against the rage of grief that he is wrapped in. This is a passage of conflict, turmoil, of the search for hope amongst the indifference of that “great, vast, blank generality” – white America. He is pessimistic in his assessment, lamenting the impossible challenge of demanding “a generosity, a clarity, and a nobility which they [white Americans] did not dream of demanding of themselves.” It is in this context that he asserts:

Perhaps, however, the moral of the story (and the hope of the world) lies in what one demands, not of others, but of oneself.

Curiously, or perhaps not, Davis stops the quote here. If one reads on to the sentence immediately following, they would find a condemnation that I suspect our administration would not put in a holiday newsletter. Baldwin continues:

However that may be, the failure and the betrayal are in the record book forever, and sum up and condemn, forever, those descendants of a barbarous Europe who arbitrarily and arrogantly reserve the right to call themselves Americans.

In the full context of the eulogy, Baldwin is claiming that in the face of an immoral oppressor, our salvation must be found in what we demand of ourselves. We can not, after all, fight hate with hate. We can not dehumanize our enemy to the point that we become our enemy. But, critically, this is a message directed to the mourning activists of the day – the bus riders and the bridge marchers, the counter-sitters and the speech-makers – not to university presidents who command nearly billion-dollar endowments.

The message of self-reflection is a necessary one for those fighting for change. The principles of radical justice, peace, and equality must be self-evident in the movement and the people who deliver them before they are made a reality for the world. To this end, it is important we make demands of ourselves.

But, in isolating Baldwin’s quote, President Davis has neutered his intended message. What was a grief-stricken reminder of staying true to the principles of the fight for justice becomes nothing more than an empty platitude, an inspirational quote in the worst possible way.

It seems to this writer that to turn a grief-stricken eulogy for a monumental activist into an empty and generic call for “reflection” and “hope” is a plagiarism, a poetic injustice, a rhetorical tragedy of the worst kind. This plagiarism is even more conspicuous considering the positionality of its author. An author who has ignored the calls of students to stand against Israeli apartheid and genocide, an author who has still not condemned the Supreme Court’s decision to outlaw affirmative action, an author whose commitment to “neutrality” leaves her complicit in the worst crimes of our day.

Elizabeth Davis knows that the status quo is a powerful blanket – a shield against alumni backlash and an excuse for students who demand more of their school. So, it is fitting to end the year with such a quote that calls for individual reflection rather than societal critique. It is easy to spit out calls for “courage, moderation, justice, wisdom, and humility” while wrapped in the warm blanket of generational wealth, promoting a vague “hope” while doing little to deliver it to those who need it most. It is easy to lecture about tolerance and the value of free discourse while your communities are not being carpet-bombed; all the while, your tax dollars, your investment dollars, and your tuition dollars legitimize and support global atrocity. Of course, you can not be troubled with such matters. After all, it is far too controversial, complicated, or political to take a stand for justice while the path toward it is yet to be guarded by F-15s and a red carpet.

James Baldwin concludes the eulogy with this, a message that I wish Elizabeth Davis would have scrolled down far enough to read:

Since the American people cannot, even if they wished to, bring about black liberation, and since black people want their children to live, it is very clear that we must take our children out of the hands of this so-called majority and find some way to expose this majority as the minority which it actually is in the world. For this we will need, and we will get, the help of the suffering world which is prevented only by the labyrinthine stratagems of power from adding its testimony to ours.

No one pretends that this will be easy, and I myself do not expect to live to see this day accomplished. What both Martin and Malcolm began to see was that the nature of the American hoax had to be revealed—not only to save black people but in order to change the world in which everyone, after all, has a right to live. One may say that the articulation of this necessity was the Word’s first necessary step on its journey toward being made flesh.

And no doubt my proposition, at this hour, sounds exactly that mystical. If I were a white American, I would bear in mind that mysteries are called mysteries because we recognize in them a truth which we can barely face, or articulate. I would bear in mind that an army is no match for a ferment, and that power, however great that power may consider itself to be, gives way, and has always been forced to give way, before the onslaught of human necessity: human necessity being the fuel of history.

If my proposition sounds mystical, white people have only to consider the black people, my ancestors, whose strength and love have brought black people to this present, crucial place. If I still thought, as I did when Martin and Malcolm were still alive, that the generality of white Americans were able to hear and to learn and begin to change, I would counsel them, as vividly as I could, to attempt, now, to minimize the bill which is absolutely certain to be presented to their children. I would say: if those blacks, your slaves, my ancestors, could bring us out of nothing, from such a long way off, then, if I were you, I would pause a long while before deciding to use what you think of as your power. For we, the blacks, have not found possible what you found necessary: we have not denied our ancestors who trust us, now, to redeem their pain.

Happy Godamned Holidays