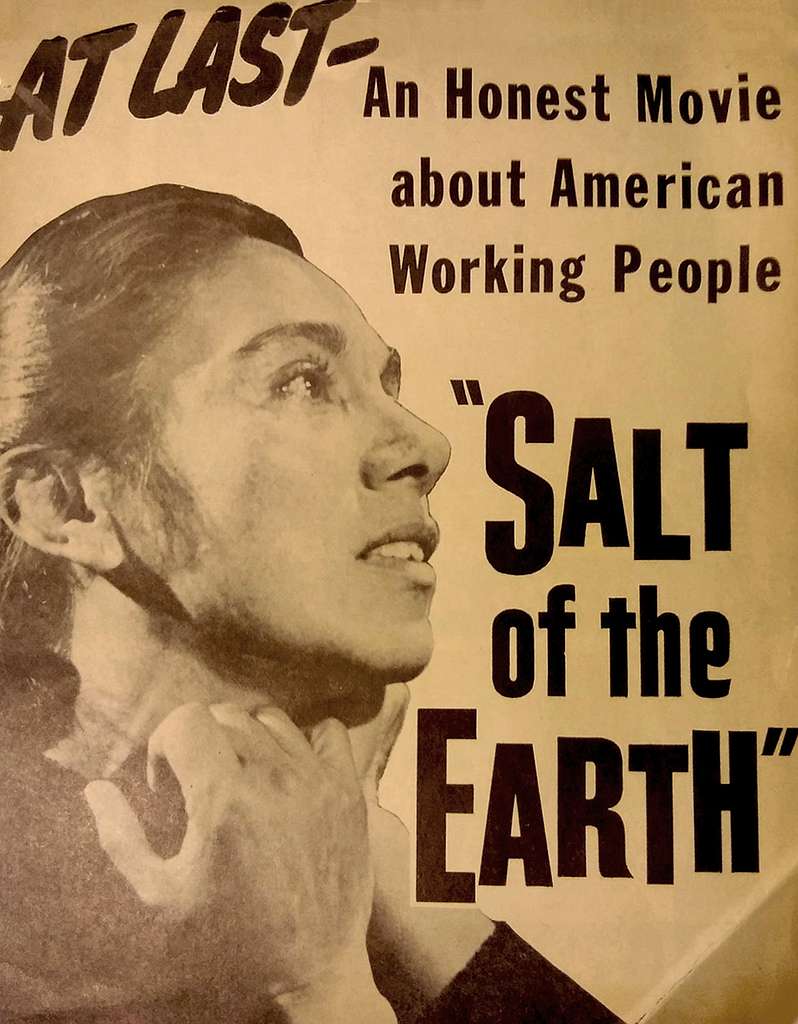

This past Friday, March 31st, Furman YDSA hosted our first movie night (of many!), featuring the 1954 neo-realist film Salt of the Earth.

“Whose neck shall I stand on to make me feel superior, and what will I have out of it? I don’t want anything lower than I am. I am low enough already. I want to rise and to push everything up with me as I go.”

Those words, perhaps the most resonant of the film, belonged to Esperanza Quintero, portrayed by Mexican actress Rosaura Revueltas. In the film, Esperanza is a Mexican-American zinc miner’s wife who takes on a leading role in a bitter strike at her husband’s mine, leading to dramatic changes in the role of women in the community as class, race, and gender collide into one great social conflagration. It all comes to a head at the film’s climax, as the entire community and workers from surrounding ones converge to stop the mine operators’ attempt to evict the striking workers from their company-owned shacks. With their sheer numbers and unflinching solidarity, they force the company to surrender to the strikers’ demands of equal pay with white workers, safer working conditions in the mines, and (at the insistence of the women) modern plumbing and heating in their homes. In the process, the community’s men set aside their wounded pride to come to the aid of their wives and sisters, and white workers from neighboring mines cross racial lines to help their fellow workers fight for that which they themselves already have. The message is clear: Workers of the world—of all genders, all races—unite! One can almost hear The Internationale play as the end credits roll.

This message is as timeless as it is revolutionary. It is radical today, and it was certainly radical in 1954. It should come as no surprise that the filmmakers could not find a Hollywood studio willing to distribute it, nor hardly any theaters that would screen it. In fact, Salt of the Earth’s entire history from conception to release is a window into the climate of rabid McCarthyist repression that dominated the era. Director Herbert Biberman was one of the “Hollywood Ten” who were imprisoned and then blacklisted from the film industry for defying McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee. Production was complicated by the fact that U.S. authorities deported Revueltas, the star actress, to Mexico before the film was complete. Anticommunist vigilantes fired at the set with rifles during production and burned down one of the actors’ homes after filming wrapped. The editors who worked on it in post-production did so in secret after hours, and the final copy was stored in secret in an unlisted shack for fear that burglars would destroy it. Upon its (very limited) release, it was loudly denounced by the press and condemned by a formal resolution of Congress. It was not long before the FBI launched an investigation into how it was funded. One of the actors, a union organizer himself, was brought to trial and convicted for violating the anti-communist oath he and all other union members had been required to sign upon the passage of the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, based on the assumption that Salt of the Earth was communist propaganda. His trial went as far as the Supreme Court before his conviction was struck down.

But as much as Salt of the Earth is a window into this country’s history of anticommunist repression, it is also a window into our own radical lineage as socialists. The events of the story are based on an actual strike, the 1951-1952 strike against Empire Zinc in New Mexico. Rather than professional actors, the director employed actual zinc miners for most of the film’s roles, and not just any zinc miners, but the actual participants in the Empire Zinc strike. These were the courageous workers of Mine-Mill Local 890, a local branch of the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers. Many of the most prominent actors were union organizers who had been front and center during the strike, including Esparanza’s husband Ramon (Juan Chacón, president of Local 890) and union steward Frank Barnes (Clinton Jencks, IUMMSW national organizer). The IUMMSW itself had a long and storied career of labor radicalism. Founded in 1893 as the Western Federation of Miners, it waged some of the most intense strikes in American history, facing severe, often violent government repression in the process. In 1905, it was one of the founding members of the revolutionary Industrial Workers of the World. In the 1930s, under its new name, it helped found the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the militant industrial-unionist alternative to the American Federation of Labor. It was known as a hotbed of Communist Party activity—its president in the 1940s and 1950s was a card-carrying Communist—for which it was eventually expelled from the CIO under pressure from the Truman administration. It won the admiration of marginalized workers and the ire of company owners and conservative union bureaucrats by denouncing the U.S. invasion of Korea and going out of its way to organize neglected Black and Hispanic workers. It was eventually worn down by decades of union-busting and division within the labor movement, but its radical legacy lives on in the frames of Salt of the Earth.As volunteers in the great historical army of emancipation that transcends borders and generations, the army of all people across space and time who have raised the red banners of freedom, justice, and solidarity, we count ourselves among the inheritors of the legacy of those who volunteered before us—comrades like the workers of Mine-Mill 890. By, for example, screening Salt of the Earth, we are celebrating that legacy, reveling in it, declaring that all the repression heaped on the shoulders of our comrades from years past means nothing in the face of a movement that lives and breathes today, a movement that has survived to honor its own history, a movement that is determined to continue to survive, because it has a lot of history left to make.

Leave a Reply